Manage AMD-Related Vision Decline

Protecting Your Vision Through Healthy Living

As we get older, it’s normal for our eyesight to change. You may find it harder to focus on close objects without reading glasses, or your eyes might take more time to adjust when lighting changes. These shifts are often manageable with corrective lenses or improved lighting. However, certain vision changes may signal an underlying eye condition.

One of the most common causes of vision loss in older Americans is age-related macular degeneration (AMD). This condition occurs when the macula — the central part of the retina responsible for sharp vision — begins to break down. As it progresses, AMD can interfere with central vision, making it difficult to see faces, read, drive, or perform daily activities.

AMD typically affects people over the age of 55. Risk factors include smoking, elevated cholesterol, high blood pressure, and a genetic predisposition. Having close family members with AMD increases your likelihood of developing it.

There are two main forms of AMD. The most frequent type, called dry or atrophic AMD, advances in stages. Early stages often have no clear symptoms. As the disease moves into the intermediate phase, you may experience slight blurring or have trouble seeing in dim light. In its later phase, AMD can introduce a hazy area or blank spots in your central vision, and colors may look washed out.

The less common form, wet or neovascular AMD, can cause rapid vision loss without prompt treatment. This occurs when unusual blood vessels grow under the retina and leak blood or fluid, harming the macula. A classic symptom is seeing straight lines appear distorted. Dry AMD can also progress into this more aggressive form.

AMD often advances slowly, allowing time to take preventive action. Catching it early offers opportunities to slow its development.

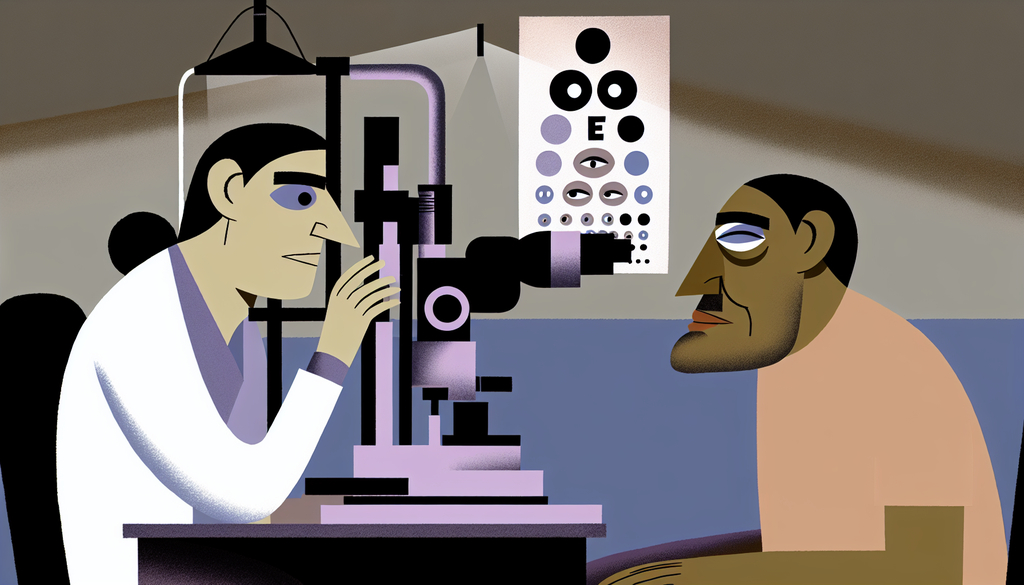

A comprehensive eye exam can spot AMD. During the test, an eye care professional uses eye drops to dilate your pupils and examine the retina. Advanced imaging methods such as optical coherence tomography may also be used to assess damage.

If you receive a diagnosis of AMD, various measures can help delay its progression. “In early and intermediate stages, maintaining a healthy lifestyle is key,” says Dr. Tiarnán Keenan, an ophthalmologist with the NIH. He emphasizes eating nutritious foods, staying active, and avoiding tobacco use. Practicing these habits may not only slow AMD but reduce your chance of developing it.

In recent developments, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the first two medications for late-stage dry AMD, both resulting from NIH-supported research. While these drugs can slow the disease, they do not stop or reverse damage already done.

For wet AMD, the standard treatment involves anti-VEGF injections administered directly to the eye. These medications help reduce abnormal blood vessel leakage and bleeding under the retina.

Researchers supported by the NIH are also studying other strategies to delay or manage AMD. One area of focus is the AREDS2 dietary supplement, which has been shown to slow progression from intermediate to advanced stages.

Another promising avenue involves stem cell therapy to preserve macular function. Scientists can convert blood cells from patients into stem cells in the lab.

“We can grow these cells and transplant them into the retina of AMD patients,” Keenan says. Clinical trials are underway to explore the success of this treatment. Find out how to get involved in the study.