How mega storm Gannon compressed Earth's plasmasphere down to just 20% of its normal size

image:

Researchers have obtained the first thorough data on how a superstorm compresses Earth's plasmasphere, shedding light on why it took more than four days to recover—an event that led to disruptions in GPS and communication networks.

Credit: Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research (ISEE), Nagoya University

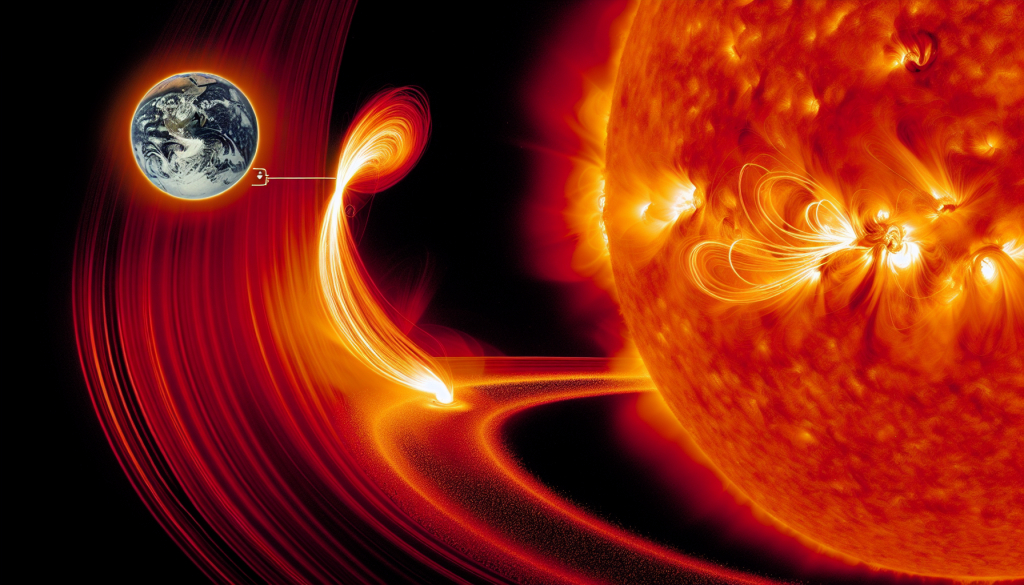

A geomagnetic superstorm is a powerful space weather phenomenon initiated when the Sun shoots vast bursts of charged particles and energy at Earth. These rare events happen only about once every two decades. On May 10–11, 2024, Earth was hit by the most intense superstorm in more than 20 years, informally named the Gannon or Mother’s Day storm.

Dr. Atsuki Shinbori and his team at Nagoya University’s Institute for Space-Earth Environmental Research led a study capturing direct measurements of this unprecedented event. Their findings offer the first detailed look at how such a storm compresses Earth’s plasmasphere—a vital zone filled with charged particles that surroundings our planet. Published in the journal Earth, Planets and Space, their work enhances understanding of how Earth's upper atmospheric layers are affected during strong space weather, improving our ability to predict technological disruptions to systems such as satellites and GPS.

Perfect timing: Arase records unique storm data

The Arase satellite, launched by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) in 2016, orbits the region occupied by the plasmasphere and monitors shifts in plasma conditions and magnetic fields. During the May 2024 superstorm, Arase was ideally situated to document the intense plasmasphere compression and its gradual return to normal conditions. This was the first time consistent, direct measurements showed the plasmasphere being forced to such a low altitude during a superstorm.

“We used data from Arase to track the plasmasphere and combined it with readings from ground-based GPS receivers to observe the ionosphere, which serves as a source of particles to the plasmasphere. Analyzing both revealed the extent of the compression and explained the unusually slow recovery,” said Dr. Shinbori.

The plasmasphere collaborates with Earth’s magnetic field to shield us from the Sun’s hazardous charged particles. Typically, it stretches thousands of kilometers into space, but during the May storm, its outer limit dropped from about 44,000 kilometers above Earth down to roughly 9,600 kilometers.

The superstorm was triggered by multiple explosive solar events ejecting vast amounts of solar material toward Earth. In just nine hours, the storm compressed the plasmasphere to one-fifth of its standard size. Recovery was unusually lengthy—stretching over four days—the longest recorded since Arase started observations in 2017.

“The storm initially caused significant heating at the poles, which then resulted in a steep reduction in the ionosphere’s particle density. This throttled the replenishment of the plasmasphere,” explained Dr. Shinbori. “Such prolonged effects can lead to GPS inaccuracies, interfere with satellites, and make space weather harder to forecast.”

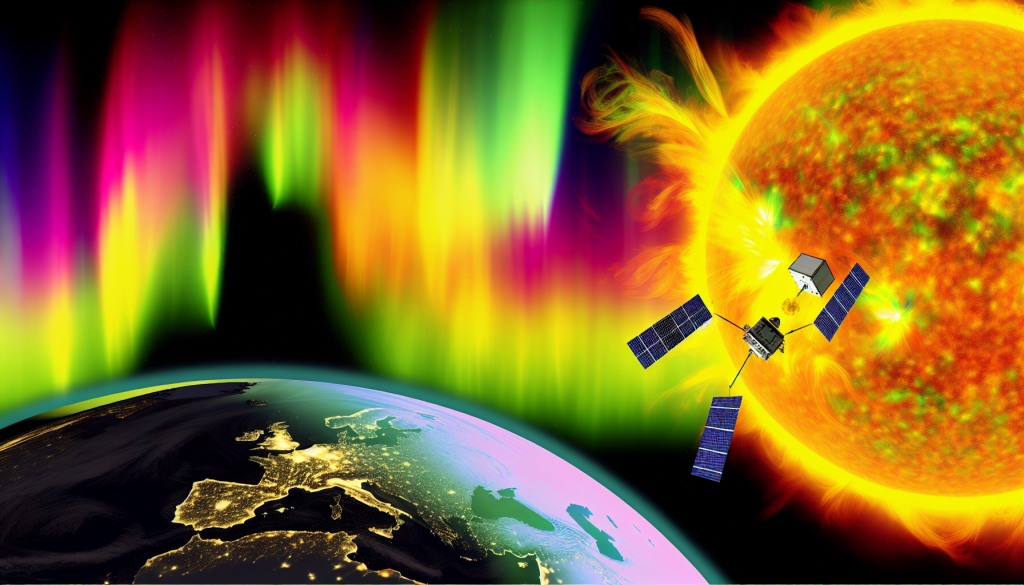

Visual confirmation: Equatorial auroras light up skies

At the storm’s peak, intense solar activity compressed Earth’s magnetic field so severely that charged particles were able to travel deep along field lines toward lower latitudes, generating vibrant auroras far from the poles.

Ordinarily, auroras are seen only in polar areas where Earth’s magnetic lines steer solar particles into the atmosphere. But the enormous force of this storm moved the aurora-creating zone away from the polar regions to areas such as Japan, Mexico, and southern Europe's skies—places that seldom witness such displays. The stronger the storm, the farther from the poles auroras can be viewed.

Negative storms delay plasmasphere recovery

Roughly one hour after the storm's onset, upper atmospheric particles intensified near the poles and flowed toward the planet’s polar regions. As the storm diminished, the plasmasphere began to regain particles drawn from the ionosphere.

Typically, this replenishment takes one to two days. However, in this instance, the process extended to over four days due to an invisible event known as a “negative storm.” In such storms, heating alters the upper atmosphere's chemical composition, reducing oxygen ions that are essential for creating the hydrogen particles necessary to restore the plasmasphere. Only satellites are capable of detecting these hidden effects.

“The negative storm hindered recovery by altering upper atmospheric chemistry, cutting off the particle supply needed for refilling,” said Dr. Shinbori. “It’s the clearest link we've seen between negative storms and delayed plasmasphere recovery.”

The data offer crucial insight into how energy and particles behave within Earth’s protective plasma environment. The May 2024 storm disabled multiple satellites, caused data transmission failures, disrupted GPS services, and interfered with radio signals. Understanding how long the plasmasphere remains compromised after a storm is vital for improving space weather preparedness and protecting space-based technologies.

Journal

Earth Planets and Space

DOI

10.1186/s40623-025-02317-3

Subject of Research

Not applicable

Article Title

Characteristics of temporal and spatial variation of the electron density in the plasmasphere and ionosphere during the May 2024 super geomagnetic storm

Article Publication Date

20-Nov-2025

COI Statement

The authors have no competing interests to disclose.