Researchers observe enzymes in motion and uncover why their movements matter

Image:

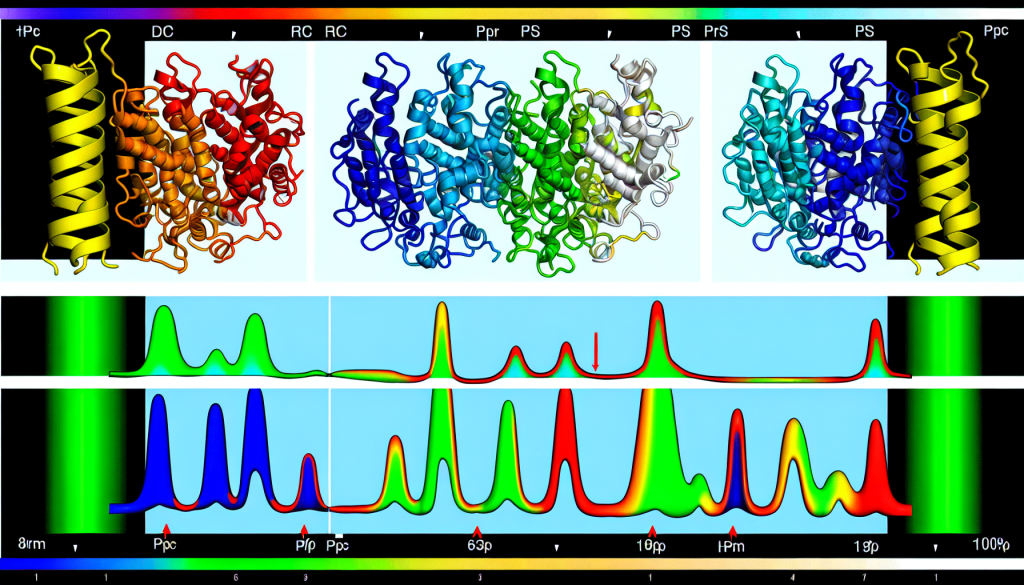

Visualization of a protein's dynamic structure. This approach combines various NMR techniques to produce a detailed map of molecular movement within a protein.

Credit: Tokyo Metropolitan University

Tokyo, Japan – Scientists at Tokyo Metropolitan University have devised a novel method for determining protein structures using Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy. This new approach highlights how distinct parts of large molecular systems, such as enzymes, move as they carry out chemical reactions. By studying a yeast enzyme, the team illustrated the critical role played by these internal molecular motions. Their technique offers a unique way to better understand how biomolecules operate and how their motion can contribute to disease.

Enzymes are vital components in biological systems, playing a role in numerous life-sustaining reactions. While high-resolution images from X-ray crystallography or cryo-electron microscopy have captured their detailed shapes, these methods provide only static views. In action, enzymes are in constant motion, shifting at the atomic level to engage other molecules and facilitate reactions. Capturing such movements, especially those occurring on ultra-small scales, remains a significant challenge in molecular biology.

Led by Associate Professor Teppei Ikeya, the research team employed NMR spectroscopy to track the movement of different enzyme segments. By combining several NMR techniques, they succeeded in mapping an “ensemble structure” – a representation of the many forms a molecule can take and their respective probabilities. This dynamic structural model reveals not just one static shape, but a complete landscape of molecular conformations.

The scientists applied their method to study yeast ubiquitin hydrolase 1 (YUH1), an enzyme responsible for recycling ubiquitin, a protein involved in regulating cellular functions. Its human counterpart, ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase (UCHL1), has been associated with neurodegenerative disorders like Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s. Using NMR, the team generated an ensemble model showcasing the enzyme’s millisecond-scale motions. They observed significant shifts in two specific areas near the active site – a flexible “crossover loop” and the N-terminus, which helps capture other proteins. The N-terminus was seen threading through the loop, transitioning through multiple states before successfully capturing a target, and then acting like a gate to secure it. The function was confirmed by how variants lacking this “gate” showed reduced enzymatic activity.

This study emphasizes the importance of enzyme flexibility and motion in their biological function. The method can be broadly applied to study other biomolecules in their native states, offering new insights into their operation and links to disease.

Funding for this research came from the Core Research for Evolutional Science and Technology (CREST) program by the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), various Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the Shimadzu Foundation, and the Precise Measurement Technology Promotion Foundation. NMR experiments were conducted using facilities supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT).

Journal

Journal of the American Chemical Society

DOI

10.1021/jacs.5c06502

Article Title

Multistate Structure Determination and Dynamics Analysis Reveals a Unique Ubiquitin-Recognition Mechanism in Ubiquitin C-terminal Hydrolase

Article Publication Date

6-Aug-2025