River otters ignore poop and parasites when dining — and that benefits the environment

video:

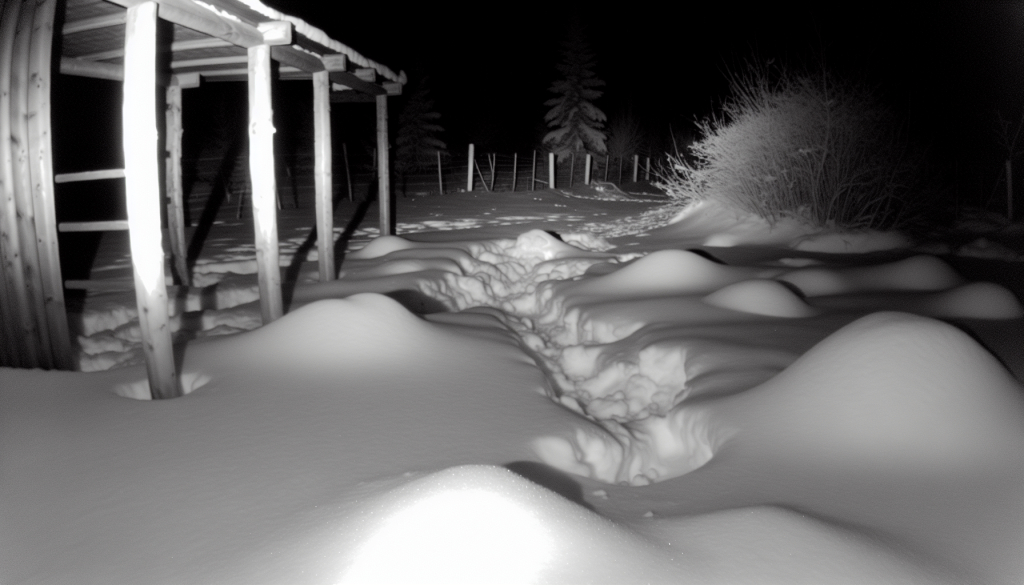

Three North American river otters are seen frolicking in the snow on the docks at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, caught on video using the center’s night-vision wildlife cameras.

Courtesy: Karen McDonald, Smithsonian Environmental Research Center

North American river otters aren't known for cleanliness—often eating, playing, and relieving themselves in the same areas. However, this less-than-ideal hygiene has a silver lining. Researchers say these habits can offer valuable insights into emerging environmental health risks. A new study, released on August 14, marks the first time Smithsonian scientists have closely examined otters’ feeding habits and latrine spots around the Chesapeake Bay. Their investigation reveals the animals frequently consume prey infected with parasites—which may actually benefit the broader ecosystem.

“River otters are top-tier predators that play significant roles in maintaining ecological balance,” said Calli Wise, lead author of the study and a research technician with the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC). “By eating parasites along with their prey, otters may help reveal the health of their surroundings.”

Despite their importance, river otters remain among the most mysterious creatures in the Chesapeake Bay area. Their nocturnal and semi-aquatic lifestyles make them difficult to observe, and they generally keep their distance from humans. Historically common throughout North America, otter populations declined due to overhunting and habitat destruction. A reintroduction effort in Maryland during the 1990s helped boost their numbers, but scientists still have limited data about their exact population size or habits in the region.

“It’s surprising how much we still don’t know about their behavior and ecological role,” said Katrina Lohan, a study co-author and head of SERC’s Coastal Disease Ecology Lab.

Because direct observation is challenging, researchers study what otters leave behind—specifically their feces. Otters leave the water to gather at designated areas called latrines—spots where they eat, interact, and deposit droppings that serve as scent markers. By analyzing these remains, scientists get a better understanding of the otters’ diets and health.

This latest research, published in the journal Frontiers in Mammal Science, analyzed scat from 18 active latrines located on SERC’s campus in Edgewater, Maryland. Most of these sites were natural settings like riverbanks and beaches, while others were found on manmade structures such as docks and boardwalks. Scientists retrieved the fecal samples for lab analysis using DNA sequencing techniques, including metabarcoding, and examined them microscopically.

Fish and crabs made up the majority of the otters’ diet—comprising 93% of all prey identified through DNA analysis. Amphibians, worms, and occasional birds also featured in their meals. Notably, the researchers detected two invasive species in the otters’ diet: the common carp and the southern white river crayfish.

The DNA analysis also revealed numerous parasites from six distinct biological groups residing in the feces. Trematodes, or flukes, were the most common. Additional parasites included dinoflagellates and other flatworms typically found in fish gills and skin. These parasites likely infected the animals that otters consumed, rather than the otters themselves—meaning the predators probably aren’t harmed by digesting these organisms. In fact, by targeting parasite-infected fish and crustaceans, otters might help control the spread of disease among prey species. Additionally, parasites could make prey easier to catch by weakening them.

“Though parasites can negatively affect individual animals, they serve essential roles in ecosystems,” Lohan noted. “It’s possible that predators like river otters depend on these interactions to locate and capture enough food.”

Still, the researchers did uncover a few parasite species—such as roundworms and apicomplexans—that may pose risks to the otters themselves. While none of these are known to infect humans, some are related to organisms that can cause illnesses like cystoisosporiasis in people. As otters increasingly inhabit suburban and urban waterways, the chances they will encounter pathogens of concern to humans may also rise.

“Urban environments expose river otters to more pollutants and parasites that could impact both them and us,” Wise explained. “As mammals that share many similarities with humans, otters can serve as indicators of environmental health threats.”

Researchers from Frostburg State University, Johns Hopkins University, and the University of the Pacific also participated in the study. The full study will be available through the journal’s website upon publication. For additional materials or to speak with study authors, contact Kristen Goodhue at [email protected].

Journal

Frontiers

DOI

10.3389/fmamm.2025.1620318

Method of Research

Observational study

Subject of Research

Animals

Article Title

North American river otters consume diverse prey and parasites in a subestuary of the Chesapeake Bay

Article Publication Date

14-Aug-2025